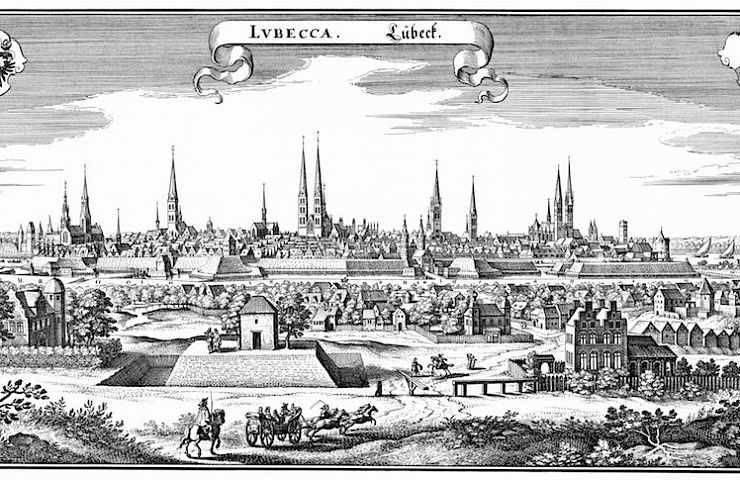

Why was the seating scheme so important? This has to do with the fact that decisions were not taken by majority vote, but were discussed until a compromise accepted by all parties had been found. This took place in such a way that after the first introductory words by the mayor of Lübeck, who normally led the negotiations at the Hansa Convention, each participant had his say in the order of the seating arrangement and submitted his vote. It is obvious that those who spoke first influenced the atmosphere and course of events more than the later speakers. In this context, one can say that seating and rank were fundamental for the type of political communication and for consensus-based decision-making.

This makes it understandable why the cities went to such great effort, equipped their delegates with many horses and expensive clothes, paid musicians and registered exactly in which form and by whom gifts of honour wine had been delivered. In this way, long before the actual meetings began, the balance of power between the cities was explored and the first stakes were set with regard to the seating arrangements during the negotiations.

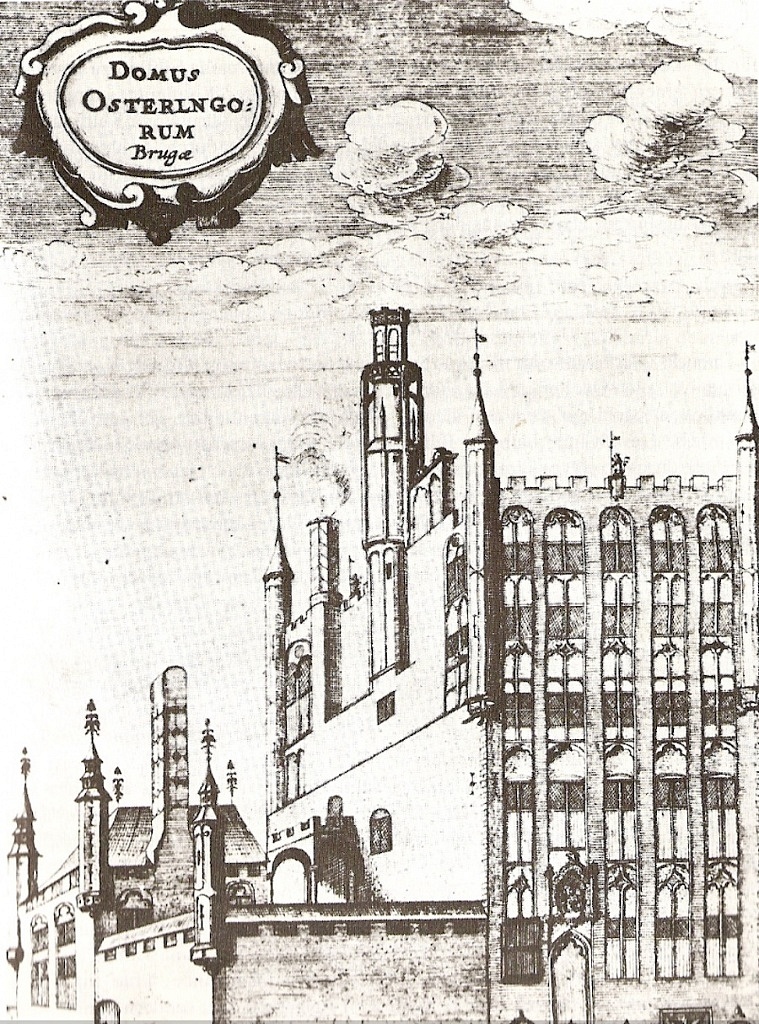

Thema auf dem Hansetag: Das Hansekontor in Brügge. Hier Versammlungsgebäude des Hansekontor in Brügge in Brügge, auch Haus der Osterlinge genannt. Scan einer zeitgenössischen Abbildung (Stich), abgebildet in Graßmann, Lübeckische Geschichte, 1989, S. 215 ISBN 3 7950 3203 2 aus dem Bestand des Archiv der Hansestadt Lübeck

What topics and problems were discussed at the Hanseatic Conference? On the one hand, the situation at the foreign trade centres of the Hanseatic League repeatedly took up a lot of attention, as was the case at the Hansa Convention of 1518: here, for example, the long-discussed question of whether one would not do well to bow to the changed market conditions in Flanders and move the Hanseatic office from Bruges to Antwerp. In addition to such trade-related issues, an explosive political issue was on the agenda in 1518. This has already been mentioned. The Hanseatic cities were confronted with an increasingly anti-urban policy on the part of the aristocratic provincial and municipal lords, who sought to limit the far-reaching political scope of their sub-ordinate cities. They wanted to force the cities back under their rule, and they had already succeeded in doing so with Stendal, Salzwedel, Halberstadt, Halle and a few others. So the danger was very realistic and the participants of the Hansa Convention were painfully aware of it. In order to improve their position in the face of the strengthening regional sovereigns, they wanted to form a political alliance within the Hanseatic League. Central point of the alliance draft was the mutual assistance and support.

(a) in the case of urban disturbances; and

b) in case of attacks by the city lord.

This help should not be of a military nature, but in the form of money donations, because – as the mayor of Göttingen put it – if you have money, then you probably get what you want, a saying that has lost nothing of its topicality to this day. And who is surprised, it was exactly because of the money that in 1518 one could not get any further in this matter. If the amount of aid to be paid seemed too low to some, it was already much too high to others. An agreement was not in the offing.

But what was finally agreed in 1518 was the question of which cities were to participate in this alliance at all and thus also participate in the Hanseatic congresses and which not. One introduced a divided membership and distinguished thereby into larger and smaller Hanseatic cities. From then on, only larger cities, whose political independence from the city lord was undoubtedly given, were to be admitted to the Hanseatic League. The other, mostly smaller cities should still be allowed to use the Hanseatic privileges in trade, but should no longer be involved in forming Hanseatic politics and therefore no longer be invited to the Hanseatic Days. This newly created group of smaller Hanseatic cities included twelve cities in 1518: Braunsberg, Stettin, Uelzen, Gollnow, Stavoren, Bolsward, Lippstadt, Unna, Hamm, Warburg, Bielefeld and Venlo.

It was not a question of excluding these smaller cities from the Hanseatic League, but of restricting the circle of politically influential cities in such a way that the secrecy of one’s own politics and defence strategies against the aristocratic sovereigns of the city and the country would be preserved. This is another facet of the Hanseatic Days of that time: In addition to great spectacle and sophisticated forms of political decision making, the ability to reorganise internal structures and adapt them to current political necessities and needs through, for example, the introduction of two-part membership.

Deutsch

Deutsch

Pingback: Hansetage in Lübeck 3 - Balticsea-Report